My mother didn't know how he killed himself, and she didn't much care.

She was happy that he did it.

She had never met him, but she had felt his fist across her face, his whip across her back. She was taken to Germany as a Polish slave laborer after watching her mother, her sister Genja, and Genja's baby daughter murdered. My mom escaped by jumping through the window and escaping into a forest. The Nazis caught her pretty soon after that.

My mother didn't talk much about what happened to her and her family. When I was a kid, I thought her silence came from annoyance with my questions about the war. Later, I realized that she didn't talk about her experiences because she wanted to protect me from the terrible things that happened, even though I was a grown man and a teacher.

Here's a poem I wrote about what Hitler did to my mom and her family.

My Mother was 19

Soldiers from nowhere

came to my mom’s farm

killed her sister Genja’s baby

with their heels

shot her momma too

One time in the neck

then for kicks in the face

lots of times

They saw my mother

they didn’t care

she was a virgin

dressed in a blue dress

with tiny white flowers

They raped her

so she couldn’t stand up

couldn’t lie down

couldn’t talk

They broke her teeth

when they shoved

the blue dress

in her mouth

If they had a camera

they would’ve taken her picture

and sent it to her

That’s the kind they were

Years later she said:

Let me tell you,

God doesn’t give

you any favors

He doesn’t say

now you’ve seen

this bad thing

and tomorrow you’ll see

this good thing

and when you see it

you’ll be smiling

That’s bullshit

__________________

The poem appears in my book about my parents, Echoes of Tattered Tongues.

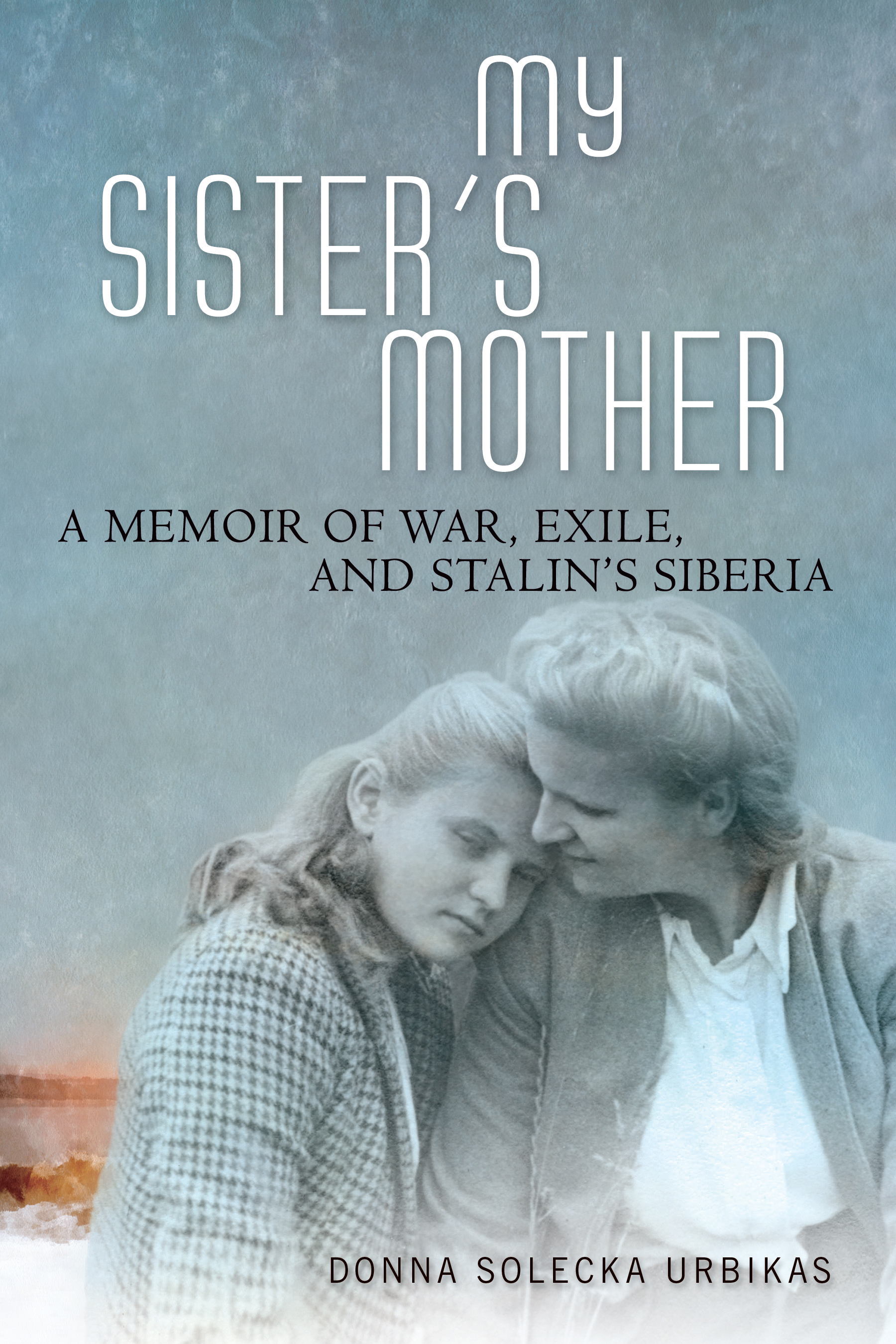

The photo was taken by my wife Linda in 1979 or so. From left to right in the back row, it's my dad, my mom, my sister Donnna, her daughter Denise, and me. In the front row are my sister's daughters Kathie and Cheryl.

If you want to read one of my poems about Hitler's Suicide Day, you can click on this link.