My wife Linda and I were showing Chicago to her brother Bruce who was visiting from the east. We were driving around the University of Chicago area on the southside of Chicago, and Bruce was saying, "Say this is a pretty campus, what kind of people teach her?"

I was driving and started in, "Well, this is one of the great universities in the world. There are probably more Nobel Laureates teachng here than in any other school in the midwest."

Bruce is a scoffer and he said, "Yeah, like who, any names an average guy would recognize?"

I'm driving around these narrow streets around the school and trying to avoid hitting anybody because it's a Saturday and people are walking to and from shopping.

Bruce thinks I'm ignoring him and he says again, "So name some of these Nobel guys!"

I say, "Well, one of my favorite writers is Saul Bellow and he won the Nobel prize and he teaches here."

And Bruce says, "Yeah? What's he like."

And I slam on the brakes to avoid hitting a guy with two bulging grocery bags who just stepped into the intersection, and I say to Bruce, "That's him. The guy I almost hit. Saul Bellow!"

And Bellow must've heard me call his name because he looked up at me and smiled, and nodded his head.

I felt a blessing descend on me, a connection I'd never forget.

I was the man who did not kill Saul Bellow.

My Parents' Experiences as Polish Slave Laborers in Nazi Germany and Displaced Persons after the War

Monday, July 24, 2017

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

Polish Mushrooms

Polish Mushrooms

I remember my mom once opening a plastic bag with dried mushrooms that came all the way from Poland. She put them in a broth, and while it was heating she talked about how Polish mushrooms were like no other food on earth.

I was a kid, maybe 7 years old, and I expected them to taste like the greatest chocolate cake in the world.

You can imagine I was disappointed.

But when my mother finally poured the mushrooms and broth into our bowls, she smiled first and then she started to cry.

_____________

Years later, when she was in her 70s and I was in my 40s, she told me about what her home in Poland was like before the war, the woods around the house, and the things she loved about those woods.

I wrote a poem about it.

Like any poem, it doesn't capture the truth of what she remembers, but now that my mom is gone, it's all I have.

My Mother Before the War

She loved picking mushrooms in the spring

and even when she was little she could tell

the ones that were safe from the ones that weren’t.

and even when she was little she could tell

the ones that were safe from the ones that weren’t.

She loved climbing the tall white birch trees

in the summer when her chores in the garden

and the kitchen were done. She loved to ride

her pet pig Caroline in the woods too

or sit with her and watch the leaves fall

in the autumn. She felt that Caroline

was smarter than her brothers Wladyu and Jan,

but not as smart as Genja, her sister

who was married and had a beautiful baby girl.

in the summer when her chores in the garden

and the kitchen were done. She loved to ride

her pet pig Caroline in the woods too

or sit with her and watch the leaves fall

in the autumn. She felt that Caroline

was smarter than her brothers Wladyu and Jan,

but not as smart as Genja, her sister

who was married and had a beautiful baby girl.

My mother also loved to sing.

There was a song about a chimney sweep

that she would sing over and over;

and when her father heard it, he sometimes

laughed and said, “Tekla, you’re going to grow up

to marry a chimney sweep, and your cheeks

will always be dusty from his dusty kisses.”

But she didn’t care if he teased her so.

There was a song about a chimney sweep

that she would sing over and over;

and when her father heard it, he sometimes

laughed and said, “Tekla, you’re going to grow up

to marry a chimney sweep, and your cheeks

will always be dusty from his dusty kisses.”

But she didn’t care if he teased her so.

She loved that song and another one,

about a deep well. She loved to sing

about the young girl who stood by the well

waiting for her lover, a young soldier,

to come back from the wars far away.

about a deep well. She loved to sing

about the young girl who stood by the well

waiting for her lover, a young soldier,

to come back from the wars far away.

She had never had a boy friend, and her mom

said she was too young to think of boys,

but Tekla didn’t care. She loved the song

and imagined she was the girl waiting

for the soldier to come back from the war.

said she was too young to think of boys,

but Tekla didn’t care. She loved the song

and imagined she was the girl waiting

for the soldier to come back from the war.

________

The poem is from my book about my parents, Echoes of Tattered Tongues.

Wednesday, July 12, 2017

My Mother and Her Neighbors

Tens of thousands of Poles in Eastern Poland were killed between 1943 and 1944 by Ukrainian Nationalists working with their German colleagues. July 11 was the day of the worst killing, a day when the Nationalists attacked 100 or so villages. That was seventy-four years ago.

My mother's family was killing during this period by her Ukrainian neighbors. Her mother was murdered, her sister was raped and killed, her sister's baby kicked to death. My mother, a girl of 19 at the time, was able to survive by breaking through a window and running into a forest to hide. She was found a couple days later and taken to a slave labor camp in Germany. She spent the next 2 years in those camps.

My mom and my dad went back to her village in 1988 to see if she could find the graves of her mom and sister and the sister's baby. There were no graves. The men who did the killing didn't take the time to dig graves and put up crosses or markers.

During that trip, my mom made it to her old house, the one where the killing took place. She knocked on the door and when someone answered her knocking, she introduced herself and told them that she had lived in this house when she was a girl, before the killings.

The person who answered the door, a Ukrainian fellow about my mom's age, said that he had been living in the house all his life and he didn't know her and didn't know what she was talking about.

My mom left and never went back.

I haven't written a lot about my mom and her Ukrainian neighbors, but I have written two poems.

The first is called "My Mother was 19," and it's about the day the Nazis and her neighbors came to her house and did their killing.

The second poem is "My Mother's Neighbors." It's a poem of mine that has never been published. It tells about what the killers did after they left my mom's house.

My Mother was 19

Soldiers from nowhere

came to my mom’s farm

killed her sister Genja’s baby

with their heels

shot her momma too

One time in the neck

then for kicks in the face

lots of times

They saw my mother

they didn’t care

she was a virgin

dressed in a blue dress

with tiny white flowers

They raped her

so she couldn’t stand up

couldn’t lie down

couldn’t talk

They broke her teeth

when they shoved

the blue dress

in her mouth

If they had a camera

they would’ve taken her picture

and sent it to her

That’s the kind they were

Let me tell you:

God doesn’t give

you any favors

He doesn’t say

now you’ve seen

this bad thing

and tomorrow you’ll see

this good thing

and when you see it

you’ll be smiling

That’s bullshit

_____________________

My Mother’s Neighbors

Their clothes are wet and cold with the blood

of the baby and the women they helped the Germans

kill in the barn. But they won’t remember that.

They’ll only remember this walk home, the snow

falling fast around them, muting the clicking trees

and silencing the birds. They will remember

their slow talk, the old men going on about

how the potatoes they gathered this year

could never match the weight of last year’s harvest

the young men trying to hide their joy

by whispering about the village girls

and what they have seen beneath their dresses.

Later they will all be home. Already their wives

And mothers watch for them at the windows,

Afraid the snow will catch them far from home.

___________________________________

I've posted a lot of blogs about my mom over the years. This is a recent one about remembering her on the anniversary of her death: Remembering My Mom.

If you want to read more about the massacre, here is a wikipedia piece.

If you want to read more about my mom and dad, my book Echoes of Tattered Tongues is available from Amazon. Just click here.

If you want to read more about the massacre, here is a wikipedia piece.

If you want to read more about my mom and dad, my book Echoes of Tattered Tongues is available from Amazon. Just click here.

Monday, July 10, 2017

Dreams of Warsaw, 1939

The First Poem I Wrote about My Parents

I've been writing poems for about 37 years now. I started when I was in grad school at Purdue working on my Ph.D. It was a hot, humid August afternoon, and I was sitting at a desk thinking about Faulkner, trying to make sense of a line of imagery that seemed to thread through all of his novels. I wasn't having any luck.

Out of nowhere, I had this sense of my parents and where they were and what they were doing.

It came as a shock this sense. I hadn't lived at home in almost a decade, seldom saw my parents, tried in fact not to think about them and their lives. I didn't want to know about their worries, their memories of WWII and the slave labor camps and the mess those memories were making of their lives. But suddenly there they were in my head, and for some reason I started writing about them.

I hadn't written a poem in at least a decade either, but there suddenly I was writing a poem. And it wasn't the last. This poem about my parents started me writing poems again, and I've never stopped.

Here's the poem:

Dreams of Poland, September l939

Too many fears

for a summer day

I regulate my thoughts

and my breathing

regard the humidity

and dream

Somewhere my parents

are still survivors

living unhurried lives

of unhurried memories:

the unclean sweep of a bayonet

through a young girl's breast,

a body drooping over a rail fence,

the charred lips of the captain of lancers

whispering and steaming

"Where are the horses

where are the horses?"

Death in Poland

like death nowhere else‑‑

cool, gray, breathless

__________________

The poem appears in Echoes of Tattered Tongues.

The illustration above is by the Polish artist Voytek Luka. It was done as an illustration for my book Third Winter of War: Buchenwald.

Tuesday, July 4, 2017

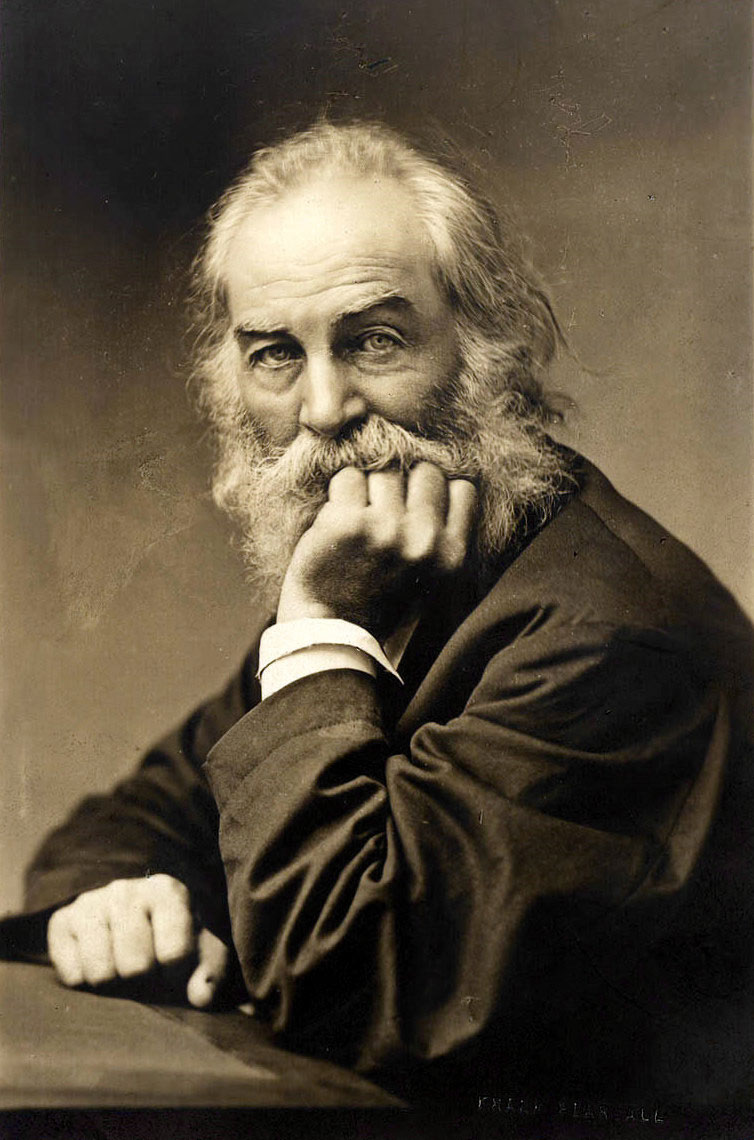

Me and Whitman

Today is the anniversary of the first

publication of Leaves of Grass back in 1855.

This book was my bible, my pal, my diary when

I was in my late teens and early 20s.

I carried a copy with me wherever

I went. I would sneak it open in the classroom when the biology professor wasn't looking, and I would read it on the L trains as they criss-crossed the skies of Chicago.

And he never left me!

Here's a poem about me and

Walt and that time and this time.

It appeared recently in the Beltway Poetry Quarterly.

AN OLD MAN LISTENING TO A

YOUNG MAN

LISTENING TO WHITMAN

He spoke to me in the desert

Outside of Elko, Nevada,

Back forty-some years ago.

Outside of Elko, Nevada,

Back forty-some years ago.

Maybe I was asleep

Or maybe I was dreaming.

I don’t remember now.

Or maybe I was dreaming.

I don’t remember now.

I was lying on the hard sand,

The billion names of God shining

Above me in the darkest sky.

The billion names of God shining

Above me in the darkest sky.

I was alone there. Not even

A book of poems with me,

When Whitman whispered,

A book of poems with me,

When Whitman whispered,

“Arise and sing naked

And dance naked

And visit your mother naked

And dance naked

And visit your mother naked

“And be funny and tragic

and plugged in, and embrace

the silent and scream for them

and plugged in, and embrace

the silent and scream for them

“And look for me beneath

the concrete streets beneath

your shoeless feet in Chicago

the concrete streets beneath

your shoeless feet in Chicago

“And ask somebody to dance

The bossa nova and hear him or her say

Sorry I left my carrots at home

The bossa nova and hear him or her say

Sorry I left my carrots at home

“And be a mind-blistered

astronaut

With nothing to say to the sun

But—Honey I’m yours.”

With nothing to say to the sun

But—Honey I’m yours.”

That’s the kind of stuff

Whitman was always whispering,

On and on, stuff like that.

Whitman was always whispering,

On and on, stuff like that.

And I got up and searched

In my backpack for a candy bar,

Chewed it ‘til there was nothing left

In my backpack for a candy bar,

Chewed it ‘til there was nothing left

And then I hitched up the

road

Out of that silence

Back to the city I grew up in,

Out of that silence

Back to the city I grew up in,

Its blocks of blocks of

bricks

And its old people in their factories

Who went to Church and got drunk

And its old people in their factories

Who went to Church and got drunk

Who hurt the ones they loved,

Who wondered who made them,

Who lived and died in due time

Who wondered who made them,

Who lived and died in due time

Monday, July 3, 2017

Coming to America

Coming to America

When I asked my mother what we had when we came from the refugee camps in Germany, she shrugged and started the list: some plates, a wooden comb, some barley bread, a crucifix, two pillows and a frying pan, letters from a friend in America.

We were as poor as mud, she said, and prayed for so little: to find her sister, to work,

to not think about the dead, to live without anger or fear.

When I asked my mother what we had when we came from the refugee camps in Germany, she shrugged and started the list: some plates, a wooden comb, some barley bread, a crucifix, two pillows and a frying pan, letters from a friend in America.

We were as poor as mud, she said, and prayed for so little: to find her sister, to work,

to not think about the dead, to live without anger or fear.

Sunday, July 2, 2017

What Elie Wiesel Knew

|

Today is the first anniversary of the death of Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and author.

Here is a poem I wrote last year when I heard he had died. It was published in the journal New Verse News.

WHAT ELIE WIESEL KNEW

Death is the air we breathe.

The bread we chew.

The brother and sister

who stand by us always.

Elie Wiesel knew this

And taught us this

Everyday.

Don't be afraid.

Saturday, July 1, 2017

Memory

Memory

I once had the immigration cops come to my family's apartment in the Humboldt Park area of Chicago. This was when I was like 13.

I answered the door and two of the cops stood there with their guns drawn shouting "Romerez, get down on the floor!"

I was a kid. I didn't say anything. I just dropped to the kitchen tile as fast as I could, and then I shouted back, "I'm not Romerez. He's in the other 2nd floor apartment."

They looked at me for a moment and turned around and kicked in the door across the hall.

This was in 1961.

Romerez was a Mexican guy who lived with his family across the hall. I used to play with his kids, hide and go seek, and tag.

I never saw any of them again.

I once had the immigration cops come to my family's apartment in the Humboldt Park area of Chicago. This was when I was like 13.

I answered the door and two of the cops stood there with their guns drawn shouting "Romerez, get down on the floor!"

I was a kid. I didn't say anything. I just dropped to the kitchen tile as fast as I could, and then I shouted back, "I'm not Romerez. He's in the other 2nd floor apartment."

They looked at me for a moment and turned around and kicked in the door across the hall.

This was in 1961.

Romerez was a Mexican guy who lived with his family across the hall. I used to play with his kids, hide and go seek, and tag.

I never saw any of them again.