The Dead are Dead

Death was a wind and a flood.

It came in the night and it came in the light.

It broke the children and their parents, the mothers who smiled and the fathers who worked in the fields.

Death broke them and buried them and scattered dust over their graves and told a story about death and the road it takes to heaven.

The dead listened and wrote the stories down and kept them close to their hearts.

They knew a story is hope.

--------------------------------

The above is part of a sequence of poems called My Mother's Death -- a sonnet. More of the poem appears at the James Franco Review.

My Parents' Experiences as Polish Slave Laborers in Nazi Germany and Displaced Persons after the War

Saturday, December 19, 2015

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

A Story My Mother Told Me

My mother spent 3 years in the slave labor camps in Nazi Germany. Here is a story she heard from one of the other Polish women there.

A Story My Mother Heard in the Slave Labor Camp

They took me from my children, three little ones, Jan was 3, Wlad 5, and Sasha 6.

They said the children would be useless on the farm in Germany. They were too young to do anything but cry and plead for food.

I begged the soldiers to let me take them with me. I said I could care for them and do the work both. I even dropped on my knees and wept, clung to their boots but they said no.

I asked them who would feed them, and they said that surely a neighbor would.

I couldn’t stop weeping, and they said if I didn’t stop they would shoot the children.

So I left them behind in Dębno.

A Story My Mother Heard in the Slave Labor Camp

They took me from my children, three little ones, Jan was 3, Wlad 5, and Sasha 6.

They said the children would be useless on the farm in Germany. They were too young to do anything but cry and plead for food.

I begged the soldiers to let me take them with me. I said I could care for them and do the work both. I even dropped on my knees and wept, clung to their boots but they said no.

I asked them who would feed them, and they said that surely a neighbor would.

I couldn’t stop weeping, and they said if I didn’t stop they would shoot the children.

So I left them behind in Dębno.

Friday, December 4, 2015

Nazi Artifacts and Memorabilia

I was

reading a fine essay by Matthew Vollmer about visiting the home of a man who collected Nazi

artifacts and memorabilia, and it got me to remembering.

I had nazi relics/artifacts when

I was a kid.

I was born in 1948 in a refugee

camp in Germany, and I grew up in the 50s, in a neighborhood of Holocaust

survivors and Polish refugees. I knew Polish cavalry officers, hardware store

clerks with Auschwitz tattoos, men who had lost their hands in the Warsaw

uprising, Polish women who had walked from Siberia to Iran to escape the

Soviets.

My friends were the children of

these people, and all of us had artifacts from the war--knives, arm bands,

watches, gas masks, helmets, etc. We traded them, brought them home, played

with them, never considering that our parents had been beaten and raped by the

men who wore these things.

I remember one time, when I

was probably 10, coming home with a dark blue Nazi helmet on my head. My father

opened the door and started to weep.

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

SUFFERING

I've given a lot of thought and feeling to suffering over the years. My father spent 4 years in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany, my mother spent three years there as a slave laborer. They were people who knew genuine and constant suffering, suffering that they were afraid would not end until it killed them. My father had seen friends beaten, hanged, castrated and crucified. My mom had seen her mom and sister raped and murdered, her sister's baby kicked to death.

Both of them carried the scars of the suffering all their lives. My dad’s scars were psychological and physical. My mom’s were mostly psychological. Did the suffering make them better people, people closer to God, people uplifted? I don’t think so.

What the suffering taught them was that the world was too often a terrible place, a place where what you most held dear was liable to vanish in a cold wind. I don’t think either of my parents thought that sorrow was a gift that God gives us. My parents were uneducated people, farm people. Suffering was a prod used to teach the recalcitrant horse or cow or mule to do what you wanted it to do. If my parents were lucky, the guards in the labor camps would use suffering only this way, as a prod.

If my parents and the other people in the camps weren’t lucky, the guards would impose suffering just for the pleasure of it. My father told me about the January night when the men from his barracks were chased out and made to stand in the snow and cold so that the guards could enjoy watching men fall to their knees and freeze to death. My mother told me about the woman guard who threw an infant into the wind and shot it for sport.

If my parents and the other people in the camps weren’t lucky, the guards would impose suffering just for the pleasure of it. My father told me about the January night when the men from his barracks were chased out and made to stand in the snow and cold so that the guards could enjoy watching men fall to their knees and freeze to death. My mother told me about the woman guard who threw an infant into the wind and shot it for sport.

Suffering of all kinds was to be avoided.

And what should you do if you see some one suffering?

Here's what my father taught me:

He believed life is hard, and we should help each other. If you see someone on a cross, his weight pulling him down and breaking his muscles, you should try to lift him, even if only for a minute, even though you know lifting won’t save him.

_______________

Here's a link to more info about my forthcoming book about my parents: Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded.

_______________

Here's a link to more info about my forthcoming book about my parents: Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded.

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Paris

Bad People

People being evil? Why do they do it?

I don't know. But they seem to be doing it a lot more. There was that book that came out last year or the year before about how civilization is more civilized than it was in the old days.

I find that hard to believe. I remember giving a reading/presentation about my parents for a class of college students studying genocide. I don't know if the students learned anything but I learned that more people have died of genocide since the UN establised it's policies against genocide in the early 1950s than died in the Holocaust.

I'm always astonished when I find out stuff like that. I look around my house and my neighborhood and my city and my state and my country, and I see that sure there's some bad people here and there but where are the millions of bad people who are ready to kill millions of their neighbors.

One of my favorite journalists is Rszyard Kapuscinski (a Pole who grew up under communism) who wrote a book called Shadow of the Sun about his travels among the genocidists of Africa. He went here and he went there trying to track down the causes of the killing. They were always absurd, meaningless, trivial.

What I took away from that book is that people can do bad things for the most absurd, meaningless, trivial reason and no law of God or man can stop them.

My father felt that all Germans were evil. When I was a kid, he wouldn't let me play with kids with German names like Mueller or Rickert or Hauser.

Was he right? I asked my mother what she thought of the Germans. She said some were good, some bad.

I guess that's what we have to remember. Some people can be bad, will be bad.

So here I am a 67 year old still trying to sort out the truths my parents left me.

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

76th Anniversary of the Start of WWII

The following is an essay that will appear in Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded, my forthcoming book about my parents and their experiences in WWII and after the war. The book will be published in March 2016 by Aquila Polonica.

When you read about history in the history books, it’s all so clear. The numbers make it seem that way. Numbers, people say, don’t lie. A thing begins on a certain date, and it ends on another particular date. You see the beginning of a thing, and you see its end. It all seems neat and clean, but it isn’t really.

The history books, for instance, tell us that World War II began on September 1, 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland from the west, and the same books tell us that the war in Europe ended almost six years later on V-E day, May 8, 1945.

When you read about history in the history books, it’s all so clear. The numbers make it seem that way. Numbers, people say, don’t lie. A thing begins on a certain date, and it ends on another particular date. You see the beginning of a thing, and you see its end. It all seems neat and clean, but it isn’t really.

The history books, for instance, tell us that World War II began on September 1, 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland from the west, and the same books tell us that the war in Europe ended almost six years later on V-E day, May 8, 1945.

My father Jan Guzlowski was not a student of history. He never had any kind of formal education, never went to school, never could read much beyond what he could read out of a prayer book, but he knew history. He had lived through history. He was a teenager working on his uncle’s farm in Poland when the Nazis invaded and turned his whole world upside down. I guess you can say he learned history from the ground up. He was captured by the Nazis in a roundup in 1940 and sent to Germany. Like a lot of other Poles, he spent the next five years at hard labor in concentration and slave labor camps there.

But for him, the war didn’t end when his camp was liberated sometime at the end of March 1945, and it didn’t end on Victory-in-Europe Day, May 8, 1945, and it certainly didn’t end when my family finally came to the US as refugees, Displaced Persons, in June 1951.

The war was always with him and with my mother Tekla Guzlowski, a woman who spent two years in the slave labor camps in Germany and before that had seen the other women in her family raped and murdered by the Nazis. The trauma of what she had seen never left here. When I was growing up, I could see it in her eyes and the way she held herself together. My parents carried with them the pain of war and its nightmares every day of their lives. In 1997, 42 years after the war ended, when my father was dying in a hospice, there were times when he wsa sure the doctors and nurses trying to comfort him were the Nazi guards who beat him when he was a prisoner in the concentration camp. There were also times when he couldn't recognize me and my mother and sister. He looked at us and was frightened. He thought we were there to torture him.

In 2005, toward the end of my mother's life, I told her that I was going to be giving a poetry reading and that I would be reading poems about her and my dad and their experiences in the war. I asked if there was something she wanted me to say to the audience. "Yes," she said, "Tell them we weren't the only ones."

My parents knew that the war had always been with them, teaching them the hard lessons, teaching them how to suffer grief and pain, how to be patient, how to live without hope or bread, how to survive what would kill a person in the normal course of life.

The war taught them that war has no beginning and no end.

____________________________________

Siege is a 1940 documentary short about the Siege of Warsaw by the Wehrmacht at the start of World War II. It was shot by Julien Bryan, a Pennsylvanian photographer and cameraman

Monday, July 27, 2015

Day 3 Poem for the 5 Poems 5 Days Poem-thon

Day 3 Poem for the 5 Poems - 5 Days Poem-thon

I wrote this poem about 30 years ago. We were living in Charleston, Illinois, and I was teaching at Eastern Illinois University. We had bought a house that was part of a development built in an old corn field. It was flat and the earth there was pretty much used up through generations of farming. Nonetheless, Linda and I tried to grow trees and roses and flowers and tomatoes and such. Pretty much unsuccessfully. Here'a a poem from that time.

A Birch Tree Dying in Illinois

If this were New Hampshire

and I were Robert Frost

this death would go unnoticed

I'd measure a wall

and worry about the mail

my wife would kneel

at her planting

placing the seed

we will harvest later

as peas or zucchini

my daughter would circle

a pine, draw up before it

and measure herself and it

But this is Illinois

and on the lawn the birch

tree is dying, its grey

bark reddens, deepens

toward death, the dry buds

powder between my fingers

and a living birch

is as scarce as glory.

Thursday, July 9, 2015

5 Poems 5 Days -- Day 2

I've been writing poems for about 37 years now. I started when I was in grad school working on my Ph.D. It was a hot, humid August afternoon, and I was sitting at a desk thinking about Faulkner, trying to make sense of a line of imagery that seemed to thread through all of his novels.

I wasn't having any luck.

Out of nowhere, I had this sense of my parents and where they were and what they were doing. It came as a shock this sense. I hadn't lived at home in almost a decade, seldom saw my parents, tried in fact not to think about them and their lives. I didn't want to know about their worries, their memories of WWII and the mess those memories were making of their lives. But suddenly there they were in my head, and for some reason I started writing about them.

I hadn't written a poem in at least a decade either, but there suddenly I was writing a poem. And it wasn't the last. This poem about my parents started me writing poems again, and I've never stopped.

Here's the poem:

Dreams of Poland, September l939

Too

many fears

for a

summer day

I

regulate my thoughts

and my

breathing

regard

the humidity

and

dream

Somewhere

my parents

are

still survivors

living

unhurried lives

of

unhurried memories:

the

unclean sweep of a bayonet

through

a young girl's breast,

a body drooping

over a rail fence,

the

charred lips of the captain of lancers

whispering

and steaming

"Where

are the horses

where

are the horses?"

Death

in Poland

like

death nowhere else‑‑

cool,

gray, breathless

__________________

The poem appeared in Lightning and Ashes.

5 Poems in 5 Days

5 Poems in 5 Days

First Poem

Dean Pasch Patty Dickson Pieczka and Maja Trochimczyk have each tagged me to do the 5 poems in 5 days thing.

As I understand it, this means I'll be posting a poem a day for 5 days. Then I'll find someone and tag her to do 5 poems in 5 days, and on and on until the whole internet is nothing but poems and ads for James Patterson's writing workshop!

Here's the first poem. It's one that Maja Trochimczyk published in her wonderful anthology of poems about Chopin (Cherries with Chopin: A Tribute in Verse, available at Amazon).

The poem is about my dad and his love of Chopin. My dad had literally no education. He was an orphan from the age of 5 and grew up on his uncle's farm in Poland. His uncle never let him attend school, and as a result my dad had no schooling, was never introduced as a child to any kind of culture. He didn't know anything about books or art or music.

But in the concentration camp, he met professors, musicians, and artists, and one of the things they told him about was Chopin. My dad loved to listen to Chopin. He felt that he and Chopin shared a soul.

A Good Death

My father says

in time he'll learn

to listen to the Polonaise

and not hear Sikorski

or Warsaw, the hollow surge

and dust of German tanks,

in time he'll learn

to listen to the Polonaise

and not hear Sikorski

or Warsaw, the hollow surge

and dust of German tanks,

only Chopin,

his staff of clean notes

and precise legato.

his staff of clean notes

and precise legato.

His dreams will be

of crystalled trees,

papered gifts

in red half light,

the smell of warm sheds

and girls drawing milk

from waiting cows.

of crystalled trees,

papered gifts

in red half light,

the smell of warm sheds

and girls drawing milk

from waiting cows.

The snow will fall

and go unnoticed.

and go unnoticed.

________________

A Good Death first appeared in Lightning and Ashes, my book about my parents.

Thursday, June 4, 2015

D-Day

June 6 is the anniversary of the Allied invasion of Europe. It's a day that means a lot to me.

My parents were two of the 15 million or so people who were swept up by the Nazis and taken to Germany to be slave laborers. My mom spent more than two years in forced labor camps, and my dad spent four years in Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Like almost every other Pole living in Europe at that time, they both lost family in the war. My mom's mom, sister, and infant niece were killed by the Germans when they came to her village. Later, two of her aunts died with their husbands in Auschwitz.

After the war both my parents lived in refugee camps for six years before they were allowed to come to the US. My sister and I were born in those refugee camps. June 6, 1944 was the day that long process of liberation for all of us began.

I've written a lot about my parents and their experiences, and here are two poems from my book Echoes of Tattered Tongues about those experiences. The first poem is about what the war taught my mother; the second is about the spring day in 1945 when the Americans liberated my dad and the camp he was in:

What the War Taught Her

My mother learned that sex is bad,

Men are worthless, it is always cold

And there is never enough to eat.

She learned that if you are stupid

With your hands you will not survive

The winter even if you survive the fall.

She learned that only the young survive

The camps. The old are left in piles

Like worthless paper, and babies

Are scarce like chickens and bread.

She learned that the world is a broken place

Where no birds sing, and even angels

Cannot bear the sorrows God gives them.

She learned that you don't pray

Your enemies will not torment you.

You only pray that they will not kill you.

In the Spring the War Ended

For a long time the war was not in the camps.

My father worked in the fields and listened

to the wind moving the grain, or a guard

shouting a command far off, or a man dying.

But in the fall, my father heard the rumbling

whisper of American planes, so high, like

angels, cutting through the sky, a thunder

even God in Heaven would have to listen to.

At last, one day he knew the war was there.

In the door of the barracks stood a soldier,

an American, short like a boy and frightened,

and my father marveled at the miracle of his youth

and took his hands and embraced him and told him

he loved him and his mother and father,

and he would pray for all his children

and even forgive him the sin of taking so long.

_______________________________

The boy soldier in the liberation poem is in part modeled after Michael Calendrillo, my wife's uncle. He was one of the first American soldiers to help liberate a camp. His testimony about what he saw in the camps was filmed for a documentary called Nightmare's End: The Liberation of the Camps. You can see a youtube of him talking about what he saw in that camp by clicking here.

Here's a link to a presentation I gave at St. Francis College about my parents and their experiences in World War II: Just click here.

My daughter Lillian sent me the following link to color photos from before and after D-Day from Life Magazine. The photos are amazing, and a large part of that amazement comes from the color. The color gives me a shock, a good one--it takes away the distance, makes the photos and the people and places in them immediate in a profound way.

Here's the link: Life.

Another Satisfied Reader of Suitcase Charlie

Author Sandra Kolankiewicz gasps at my novel Suitcase Charlie!

You can gasp along with her! Suitcase Charlie is available at Amazon as a Kindle or a paperback. A sample chapter is also available at Amazon.

Sandra's latest book of poems is The Way You Will Go. Also available at Amazon.

Here's the title poem from that book:

Adirondacks , a cricket

chirping in the corner.

You can gasp along with her! Suitcase Charlie is available at Amazon as a Kindle or a paperback. A sample chapter is also available at Amazon.

Sandra's latest book of poems is The Way You Will Go. Also available at Amazon.

Here's the title poem from that book:

The Way You Will Go

It

will not begin with your heart

though

your fingers may go numb.

One

day you’ll know it’s time to trade

that

philosophical surf board for benefits.

You’ll

reluctantly roll your dreams

into

your pocket, where you can keep

your

hand on them all week long, especially

when

you need courage. Soon you’ll begin

to

meet other persons like you, forever

exchanging

their right with their left, wearily

shifting

one foot to the other in the grocery

store,

the dentist’s waiting room, getting their

tires

changed, similar strangers whose insides,

or

the insides of their loved ones, have acquired

some

strange price tag attached to a history

of

autoimmune dysfunction, apoplectic

collapsing,

perhaps facial tics accompanied by

obsessive

nail picking. From now on, experience

is

reduced to the actuarial projection

of

the genetic proclivities of thin skin

and

fragile bone, like a Curt Explanation

of

the obvious outcome of a clogged artery,

a

Frank Dismissal of the vagaries of night

sweats

and coated tongues, a Direct

Warning

about the consequences of

diabetes

just in the moment before the Extreme

Cancer

Tale is recounted—the details of which

only

the few ever appreciate or understand!—

as

if sickness were a language one learns

only

in its country of origin!—

all

uninsurable, unlike the vase my dear auntie

mailed

me right before she unexpectedly

gave

way, an extra $1.40, the green and white

label

she and the man in the uniform signed

together

in some modest post office in the

Wednesday, June 3, 2015

The Schuessler-Peterson Murders

My novel Suitcase Charlie begins with a Prologue, a statement from an Associated Press wire report from October 18, 1955.

The bodies of three boys were found nude and dumped in a ditch near Chicago today at 12:15 p.m. They were Robert Peterson, 14, John Schuessler, 13, and brother Anton Schuessler, 11.

They had been beaten and their eyes taped shut. The boys were last seen walking home from a downtown movie theater where they had gone to see “The African Lion.”

As I wrote in my recent essay “Suitcase Charlie and Me,” the murder of the Schuessler brothers and Bobby Peterson is at the heart of my novel Suitcase Charlie. It’s what terrified me as a kid and haunted a lot of the other kids I grew up with. Until we got older and went to high school and learned that fearing something isn’t cool, we feared stuff, and one of the fears we most felt was the fear of the person who killed John, Anton, and Bobby.

There’s not a lot actually about their murders in Suitcase Charlie. The first murder in the novel is discovered about seven months after the Schuessler-Peterson murders. So the detectives in my novel worry that it may be the same killer. They talk about how the investigation of the Suitcase Charlie murders is or isn’t like the earlier investigation. Also, people in the neighborhood of the killings wonder about a connection. Like I said, there’s not a lot about the earlier murders in my novel. My novel isn’t about them.

But I know some readers are interested in the Schuessler-Peterson case. They’ve asked me about the novel’s Prologue, so I’m going to talk a little about the case that inspired my novel.

The day the boys disappeared, Sunday, October 16, 1955, they were seen in a number of places: some buildings downtown in the Loop and some bowling alleys near their home on Montrose Avenue. The cops figured that after seeing the movie The African Lion the boys hung out downtown until about 6 pm, wandering around, seeing stuff, probably doing the kind of goofing around I talk about in my “Suitcase Charlie and Me” essay. They were spotted on Montrose at a bowling alley around 7:45 pm. One of the men working there said some older guy was talking to them, some guy who seemed friendly. The boys left a little while later and started walking and hitching down Montrose Avenue toward home.

They were last seen alive about 3 miles away, getting into a car near the intersection of Lawrence and Milwaukee. That was at 9:05 that night.

Two days later, on Tuesday, October 18, their bodies were discovered outside the Chicago city limits, in a ditch in the Robinson Woods Forest Preserve, near the Des Plaines River.

A liquor salesman was taking his lunch in a parking lot there that day. When he looked up from his sandwich, he saw what he thought was a manikin. It turned out to be the body of a young boy, naked with his eyes and mouth taped shut with adhesive tape. Near him were two other naked bodies with eyes and mouths taped. All three boys had died the same way, asphyxiation.

What followed was one of the most extensive investigations in the history of the Chicago Police Department. Between the date the boys’ bodies were found and 1960 when the Chicago Tribune ran an article updating this cold case, more than 44,000 people with some kind of information about the murders were interviewed. More than 3,500 suspects were questioned.

What followed was one of the most extensive investigations in the history of the Chicago Police Department. Between the date the boys’ bodies were found and 1960 when the Chicago Tribune ran an article updating this cold case, more than 44,000 people with some kind of information about the murders were interviewed. More than 3,500 suspects were questioned.

None of it led to the discovery of the killer of the 3 boys.

However, what did follow were some additional murders, ones that seemed to share similarities with the Schuessler-Peterson case.

December 28, 1956, a little over a year after the Schuessler-Peterson murders, two young sisters, Barbara, 15, and Patricia 13, went to the Brighton Theater on Archer Avenue to see an Elvis Presley movie, Love me Tender. Four weeks later, on January 22, 1957, their naked bodies were found behind a guard rail on a country road in an unincorporated west of Chicago. Their bodies like those of the Schuessler-Peterson boys had apparently been thrown out of a car. Unlike the boys, the girls had not died of asphyxiation. Their deaths were thought to have been caused by secondary shock due to exposure. The investigation into the cause of their deaths led nowhere.

Over the years, a number of other murders in the area have been linked to the Schuessler-Peterson killings. John Wayne Gacy, the notorious “Killer Clown” guilty of murdering at least 33 young boys, was suspected by Detective John Sarnowski, one of the detectives working the Schuessler-Peterson cold case, of possibly being involved with the murders of John, Anton, and Bobby. Brach Candy Heir, Helen Brach was also linked with the Schuessler brothers and Bobby Peterson. She disappeared in February 1977 and was declared legally dead in 1984. One of the suspects in this case was a racketeer and stable owner Silas Jayne, a man also for a while a suspect in the deaths of the Grimes Sisters.

So who killed the Schuessler boys and their friend Bobby Peterson?

The best guess is Kenneth Hansen.

His name came up during a Federal investigation in the early 1990s of arson in horse racing stables around Chicago. A number of the people being investigated told the Federal authorities that Hansen had repeatedly over the years spoken about his involvement with the killing of John, Anton, and Bobby. Prosecutors at the trial proved that Hansen picked up the boys while they were hitching, abused two of them, and then killed all three when they threatened to tell their parents. He was sentenced to 200-300 years for his crimes and died in prison in September 14, 2007.

For those people who like to re-work old crimes, there are a number of interesting facts here that should get them going:

- Hansen worked at Idle Hour Stables. That’s where the killing of the three boys took place.

- Silas Jayne, who I mentioned earlier, was the owner of the Idle Hour Stables at the time.

- Later he was a suspect in the Grimes Sisters’ murder.

- Hansen was also a suspect in the Helen Brach disappearance.

- Recently, a former head of the Cook County Sheriff’s Police has offered the theory that Hansen might have been involved in the disappearance or death of the Grimes Sisters.

If you’re interested in finding out more about these murders, doing your own preliminary detective work, a good place to start is the Chicago Tribune’s extensive online archives. They are free and easy to use and will keep your eyes going for a long time. Just Google http://archives.chicagotribune.com and put in your search phrase.

Here are some of the archival articles I found especially important. Just click on the titles.

The Trial of Kenneth Hansen.

____________

The novel Suitcase Charlie is available from Amazon as a kindle and a paperback. Just click HERE.

_____________

_____________

The first photo is by Vivian Maier, the great urban photographer. The other photos are archival.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Suitcase Charlie -- How I Came to Write the Novel

Suitcase Charlie and Me

I started writing my novel Suitcase Charlie about sixty years ago when I was 7 years old, just a kid.

At that time, I was living in a working-class neighborhood on the near northwest side of Chicago, an area sometimes called Humboldt Park, sometimes called the Polish Triangle. A lot of my neighbors were Holocaust survivors, World War II refugees, and Displaced Persons. There were hardware-store clerks with Auschwitz tattoos on their wrists, Polish cavalry officers who still mourned for their dead comrades, and women who had walked from Siberia to Iran to escape the Russian Gulag. They were our moms and dads. Some of us kids had been born here in the States, but most of us had come over to America in the late 40s and early 50s on US troop ships when the US started letting us refugees in.

As kids, we knew a lot about fear. We heard about it from our parents. They had seen their mothers and fathers shot, their brothers and sisters put on trains and sent to concentration camps, their childhood friends left behind crying on the side of a road. Most of our parents didn’t tell us about this stuff directly. How could they?

But we felt their fear anyway.

We overheard their stories late at night when they thought we were watching TV in a far off room or sleeping in bed, and that’s when they’d gather around the kitchen table and start remembering the past and all the things that made them fearful. My mom would tell about what happened to her mom and her sister and her sister’s baby when the German’s came to her house in the woods, the rapes and murders.

You could hear the fear in my mom’s voice. She feared everything, the sky in the morning, a drink of water, a sparrow singing in a dream, me whistling some stupid little Mickey Mouse Club tune I picked up on TV. Sometimes when I was a kid, if I started to whistle, she would ask me to stop because she was afraid that that kind of simple act of joy would bring the devil into the house. Really.

My dad was the same way. If he walked into a room where my sister and I were watching some TV show about World War II – even something as innocuous as the sitcom Hogan’s Heroes – and there were some German soldiers on the screen, his hands would clench up into fists, his face would redden in anger, and he would tell us to turn the show off, immediately. Normally the sweetest guy in the world, his fear would turn him toward anger, and he would start telling us about the terrible things the Germans did, the women he saw bayoneted, the friends he saw castrated and beaten to death, the men he saw frozen to death during a simple roll call.

This was what it was like at home for most of my friends and me. To escape our parents’ fear, however, we didn’t have to do much. We just had to go outside and be around other kids. We could forget the war and our parents’ fear with them. We’d laugh, play tag and hide-and-go-seek, climb on fences, play softball in the nearby park, go to the corner story for an ice cream cone or a chocolate soda. You name it. This was in the mid 50s at the height of the baby boom, and there were millions of us kids outside living large and – as my dad liked to say – running around like wild goats!

In the streets with our friends, we didn’t know a thing about fear, didn’t have to think about it.

That is until Suitcase Charlie showed up one day.

It happened in the fall of 1955, October, a Sunday afternoon.

Three young Chicago boys, 13-year old John Schuessler, his 11-year old brother Anton, and their 14-year old friend Bobby Peterson, went to Downtown Chicago, the area called the Loop, to see a matinee of a Disney nature documentary called The African Lion. Today, the parents of the boys probably would take them to the Loop, but back then it was a different story. Their parents knew where they were going, and the mother of the Schuessler boys in fact had picked out the film they would see and given the brothers the money to pay for the tickets. At the time, it wasn’t that unusual for kids to be doing this kind of roaming around on their own. We were “free-range” kids before the term was even invented. Every one of my friends was a latch key kid. Our parents figured that we could pretty much stay out of trouble no matter where we went. We’d take buses to museums, beaches, movies, swimming pools, amusement parks without any kind of parental guidance. There were times we’d even just walk a mile to a movie to save the 10 cents on the bus ride. We’d seldom do this alone, however. Kids had brother and sisters and pals, so we’d do what the Schuessler brothers and their friend Bobby Peterson did.

We’d get on a bus, go downtown, see a movie and hangout down there afterward. There was plenty to do, and most of it didn’t cost a penny: there were free museums, enormous department stories filled with toy departments where you could play for hours with all the toys your parents could never afford to buy you, libraries filled with books and civil war artifacts (real ones), a Greyhound bus depot packed with arcade-style games, a dazzling lake front full of yachts and sailboats, comic book stores, dime stores where barkers would try to sell you impossible non-stick pans and sponges that would clean anything, and skyscrapers like the Prudential Building where you could ride non-stop, lickety-split elevators from the first floor to the 41st floor for free. And if you got tired of all that, you could always stop and look at the wild people in the streets! It was easy for a bunch of parent-free kids to spend an afternoon down in the Loop just goofing off and checking stuff out.

Just like the Schuessler Brothers and their friend Bobby Peterson did.

But the brothers and Bobby never made it home from the Loop that Sunday in October of 1955.

Two days later, their dead bodies were found in a shallow ditch just east of the Des Plaines River. The boys were bound up and naked. Their eyes were closed shut with adhesive tape. Bobby Peterson had been beaten, and the bodies of all three had been thrown out of a vehicle. The coroner pronounced the cause of death to be “asphyxiation by suffocation.”

The city was thrown into a panic.

For the first time, we kids felt the kind of fear outside the house we had seen inside the house. It shook us up. Where before we hung out on the street corners and played games till late in the evening, now we came home when the first street lights came on. We also started spending more time at home or at the homes of our friends, and we stopped doing as many things on our own out on the street: fewer trips to the supermarket or the corner store or the two local movie theaters, The Crystal and The Vision. The street wasn’t the safe place it once had been. Everything changed.

And now we were conscious of threat, of danger, of the type of terrible thing that could happen almost immediately to shake us and our world up.

We started watching for the killer of the Schuessler Brothers and Bobby Peterson. We didn’t know his name or what he looked like, nobody did, but we gave him a name and we had a sense of what he might look like. We called him Charlie, and we were sure he hauled around a suitcase, one that he carried dead children in. Just about every evening, as it started getting dark, some kid would look down the street toward the shadows at the end of the block, toward where the park was, and see something in those shadows. The kid would point then and ask in a whisper, “Suitcase Charlie?”

We’d follow his gaze and a minute later we’d be heading for home.

Fast as we could.

______________________

The novel is available as a Kindle or paperback from Amazon. Just click here: CLICK.

Wednesday, April 29, 2015

Suitcase Charlie -- available!

.jpg)

Suitcase Charlie

My crime novel Suitcase Charlie is now available as a Kindle or paperback.

Here's a synopsis of the book:

May 30, 1956. Chicago

On a quiet street corner in a working-class neighborhood of Holocaust survivors and refugees, the body of a little schoolboy is found in a suitcase.

He’s naked and chopped up into small pieces.

The grisly crime is handed over to two detectives who carry their own personal burdens, Hank Purcell, a married WWII veteran, and his partner, a wise-cracking Jewish cop who loves trouble as much as he loves the bottle.

Their investigation leads them through the dark corners and mean streets of Chicago—as more and more suitcases begin appearing.

Based on the Schuessler-Peterson murders that terrorized Chicago in the 1950s.

Click here to pre-order at Amazon.

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

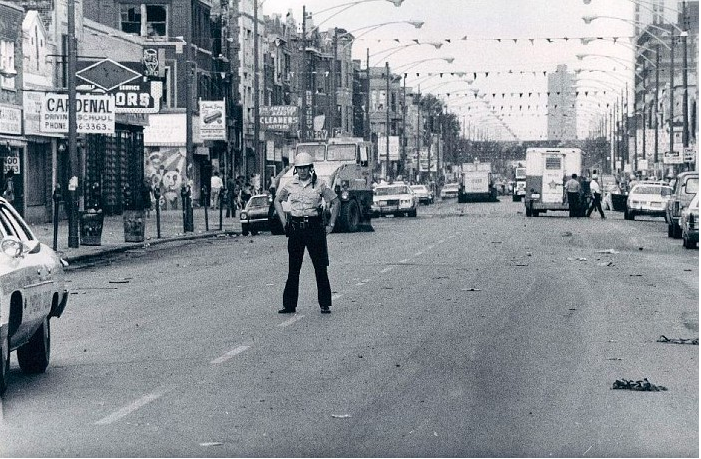

Sweet Home Chicago

I grew up in a section of Chicago that was called

Murdertown in the local papers. This was

back in the 50s, 60s, and early 70s.

My friends were beaten, stabbed, pulled from their

bicycles and cars and knocked into the street. One of my friends was dragged

out of his house by a gang and beaten with clubs until he was

unconscious. He was a good boy, kind of sissy-like with long hair and a

soft voice but a good boy. He was in the hospital for about a

month. He didn’t want to ever leave it.

One time, a man was shot dead in front of my house.

When I went outside after the police showed up to see what they were doing, a

cop called me a mother fucker and told me he’d throw my ass in jail if I didn't

get back home.

I was 12.

I went back into the house and never stepped outside

again when someone was shot in front of my house.

I carried a knife, a switchblade, in my pocket. Twice I

used it on somebody so that they wouldn't hurt me. Once it was a friend, who

was just joking around. He jumped out of an alley way when he saw me

passing. I didn't know he was joking, and I stabbed him in the stomach.

When I couldn't get a knife, I carried a hammer or a

baseball bat. The hammer was better, lighter, and I could put it in my belt.

Every couple of years there were riots. Mostly in

the summer. One time it was so bad that Mayor Daley, the old one, felt

the cops needed some back-up so he called in the National Guard. The

soldiers drove around the neighborhood in jeeps with loaded machine guns. Nights, you could hear the shooting, see

flames rolling off of apartment

buildings burning just south of us.

Three of the priests at my old parish St. Fidelis were

convicted years later of being pedophiles. They heard my confessions and told

me to say three Hail Marys and three Our Fathers. They weren't interested in

me. I wasn't pretty enough for them.

One time a gang attacked my mother and me when we were

coming home from the supermarket. This was in the

early afternoon. It was bright and warm. We were carrying shopping bags, and

they wanted to steal our food. We fought them off. My mother beat one of the

gang boys down to the sidewalk. He tried to crawl away, but she kept kicking

him and kicking him. He pleaded with his homeboys to come save him from my mom.

They wouldn't come. They were afraid. Finally, my mother stopped kicking the gang

boy, and she let him crawl away.

My mother had survived 2 years of life in a concentration

camp, and she knew how to get by in the streets of Chicago, in our old

neighborhood.

We finally had to move when the

house we had been living in was burned to the ground during a gang war in the

early 1970s.

Nobody every rebuilt on that

spot. It’s still an empty lot in Murdertown 42 years later.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)